My mother said, “If you knock all of them down I’ll buy you the bowling alley.”

When I was 10 years old my mother took my sister and I bowling at the grimy place 15 minutes from the house. A number of frames into the first game I rolled the ‘Big Four’ split, which is the two pins farthest to the left and right remaining up. ![]() I walked back a bit dejected and glanced up at the screen, showing the red circle around the ‘6.’ My mother piped up, saying, ‘Well, Zach, If you get all of them down, I’ll buy you the bowling alley.’ My heart leaped, and I looked back at the pins. My mind shot to how I could complete the spare. I had no idea it was the 6th hardest spare to complete in the game; it just looked hard, and the only way I could figure out how to do it was with a curve. I don’t throw with a curve, never have, except by accident. My mother taught me to bowl straight. When I did accidentally bowl with a curve, the ball always curved left. Although the pins were symmetrical, I ‘knew’ the best chance I had to knock them all down was to get the pins on the right to fly left. I needed to have some curve, but I also needed some help, so I lined up as far left as I could go in the lane, oriented my body left-foot out front, in an athletic stance, pointing the front of my body toward the pins, and threw the ball, twisting my wrist slightly to the right to get a little spin on the ball.

I walked back a bit dejected and glanced up at the screen, showing the red circle around the ‘6.’ My mother piped up, saying, ‘Well, Zach, If you get all of them down, I’ll buy you the bowling alley.’ My heart leaped, and I looked back at the pins. My mind shot to how I could complete the spare. I had no idea it was the 6th hardest spare to complete in the game; it just looked hard, and the only way I could figure out how to do it was with a curve. I don’t throw with a curve, never have, except by accident. My mother taught me to bowl straight. When I did accidentally bowl with a curve, the ball always curved left. Although the pins were symmetrical, I ‘knew’ the best chance I had to knock them all down was to get the pins on the right to fly left. I needed to have some curve, but I also needed some help, so I lined up as far left as I could go in the lane, oriented my body left-foot out front, in an athletic stance, pointing the front of my body toward the pins, and threw the ball, twisting my wrist slightly to the right to get a little spin on the ball.

It went in the direction I wanted as it rolled down the lane but wasn’t curving. I leaned my body to the right, willing the ball to curve at the last second as it collided with the first pin on the right, which flew over to the left, colliding with the back pin, ‘7,’ on the left at the same time it hit the back pin ‘10,’ on the right. I held my breath as the pin on the left started spinning on the lane, ever so close to the last pin standing, the front one on the left. It was visibility beginning to slow, and my heart sank. I’d almost done it; I’d nearly gotten all of them down. I turned back to my mother and sister just as the spinning pin came to a halt, the top looking like it was just about to touch the remaining pin standing. My mother had her hand to her chest, mouth agape, and my sister was laughing with her hands on either side of her face. Then my mother blurted out, “I thought I was going to have to buy you the bowling alley!” I laughed and joked, “What about part of the bowling alley?” She said, “No, no, no, it was an all or nothing sort of thing.”

Obviously, she wasn’t going to buy me the bowling alley, but that was 25 years ago, and the story lives in my family’s lore, retold nearly as often as we retell the story of my sister driving her car into the garage door. I tell this anecdote to illustrate that, as my research showed, most of the individuals I observed bowling did so to engage in a low-stress, low-effort social activity with family, friends, and acquaintances. Very few, if any, of the people I observed at bowling alleys or talked to about bowling did so to make new friends. This, more than any other finding, informs how bowling alleys should be designed, run, and function.

(MessyNessy, 2016)

This lack of socialization between groups wasn’t always the case. The culture of bowling morphed from being a social activity during the boom of socialization from the 1930s to the 1970s to a siloed activity within preset small social groups today. It was a different age. People were more willing to go out and engage in activities, more willing to meet other people and intermingle between groups.

Part of my research revealed that bowling alleys used to be a staple in the basements of churches across America, exploding in the 1940s and 1950s when bowling was in vogue, with at least 13 in the city of Milwaukee at their peak. The blog author Messy Nessy wrote, “It was the German immigrants of the 1860s who first started building them as moral refuges for their community.” The author wrote that bowling alleys functioned as social gathering spots, allowing people to drink and socialize, though, of course, the bowling alleys in churches didn’t serve alcohol before noon on Sundays.

(MessyNessy, 2016)

Americans have been steadily spending more time alone and within their enclosed social bubbles since the end of the 1960s. Derek Thompson, a writer for The Atlantic, spent a lot of time looking into the American Time Use Survey and came up with three explanations, including that ‘Many Americans have traded pets for people time,’ (Thompson, 2024) people have become much busier, and Putnam’s theory in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community that, ‘The rise of aloneness is part of the erosion of America’s social infrastructure.’ (Thompson, 2024)

Countless movies have references to each of these points. “The world got itself in a big damn hurry.” (Darabont, 1994) “Until that dog arrived on my doorstep… A final gift from my wife… In that moment, I received some semblance of hope… an opportunity to grieve unalone… And your son… took that from me” (Stahelski, et al. 2015) “I just feel so alone, even when I’m surrounded by other people.” (Coppola, 2003) Since it’s in a movie, there’s a semblance of truth and familiarity. Movies provide shared experiences and understanding when engaging in activities, but reality is different for every person who experiences it.

A quote from another movie illustrates the timelessness and the changing times for one of the oldest activities we, as Americans, have: “The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game: it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds of us of all that once was good and it could be again.” (Robinson, 1989) The movie was released in 1989, just before the height of the steroid era, the home-run race, and the great fall of baseball as America’s pastime. In 1989, it was inconceivable that none of the national sports talk shows would spend more than a few minutes an episode discussing baseball. Still, the 2023 Major League Baseball World Series was the least watched on record. (Sim, 2023)

Bowling had a similar fall as a sport, albeit much earlier. Since bowling was popularized in the 1930s, it’s difficult to quantify the changes in the industry. The easiest way to do it is by examining professional bowling. In their piece, The Rise and Fall of Professional Bowling, Zachary Crockett of Priceonomics wrote that in 1964, professional bowler ‘Don Carter was the first athlete in any sport to receive a $1 million endorsement deal…At the time, the offer was 200x what professional golfer Arnold Palmer got from his endorsement with Wilson, and 100x what football star Joe Namath got with Schick razor.’ (Crockett, 2014) Don Carter was already making $100,000 per year before that deal was signed. Later in the article Crockett posted a list of the PBA’s money list 50 years later. The top earner made $248,317.

Still, despite the perception of bowling as a dormant sport, far removed from mainstream consciousness, when I visited two bowling alleys for ethnographic research, the lanes were all full or were full within an hour of opening. I had to wait over an hour for a lane to open up the Monday after the Superbowl when many people were presumably nursing their late-night hangovers from parties the night before. The congregation of people bowling in the same place makes the activity seem alive and even sought after within the alleys themselves. Why? As mentioned in my open, people are starving for a means of socializing with their friends, families, and acquaintances in physical environments, with a means and an excuse to put their phones aside and talk to people. The ethnographic interview I conducted where my mother said, “bowling was something to do with friends” and “People bowl alone? I didn’t even know that was a thing,” convinced me that in the general public consciousness, bowling isn’t a sport, it’s an activity people do as an excuse to hang out with other people.

Despite the majority of bowlers using the activity to hang out with other people, everyone doesn’t view the activity of bowling in the same light. My mother said she was only competitive with herself in the activity, never really trying to beat someone else or someone else’s score, likening bowling to ice skating. The two ethnographic visits to bowling alleys corroborated that finding for less skilled bowlers and bowlers with families but showed a wide range of competitiveness and competition based on skill level, the size of their group, and their purpose for being at the lanes.

In general, the bowlers who scored higher, either bowled alone or in pairs and were there to practice maneuvers rather than socialize, were more competitive and concerned with their scores than social bowlers. There was also a general inverse relationship between skill level and reaction to a positive or negative result, something that my mother, in a second ethnographic interview, also noted after a bowling session.

It is important to note that although I visited two bowling alleys, I did not view a “league match.” (Cameron, 1998). It’s a hole in my research and a popular use of bowling alleys for socialization purposes on many weekday nights that would inform decisions on the design of bowling alleys in the present day. My assumption, and I note it as an assumption here, is that on average, the people rolling in bowling leagues care about their score and the ‘sport of bowling’ at least as much if not more than the serious bowlers I observed attempting different shots and maneuvers during my ethnographic observations.

Despite the above data and inputs on the changing societal norms of socialization, bowling alley lanes haven’t changed dramatically since the activity was popularized in the early 1930s. The reason is multifold, but it harkens back to the previous Field of Dreams quote, which mentioned baseball as the constant through the litany of changes America went through in the 20th century. Despite baseball fading as a sport, people grasped onto the idea of the activity as a comforting constant. Whatever else varied in their life, baseball stayed the same.

People don’t want bowling to change. Sure, machines replaced people setting pins, computers replaced manual scoring, and modern alleys have bumpers so beginners don’t throw balls straight into the gutter. Still, the essence of throwing a ball to knock 10 pins over has remained the same, even from over 100 years ago.

(Rick, 2021)

The diminishment of the sport of bowling is inarguable, but my ethnographic research showed that the popularity of bowling within bowling alleys has not waned. Based on my research, I actually argue that the supply does not reach the demand, at least in the greater Portland, Maine area.

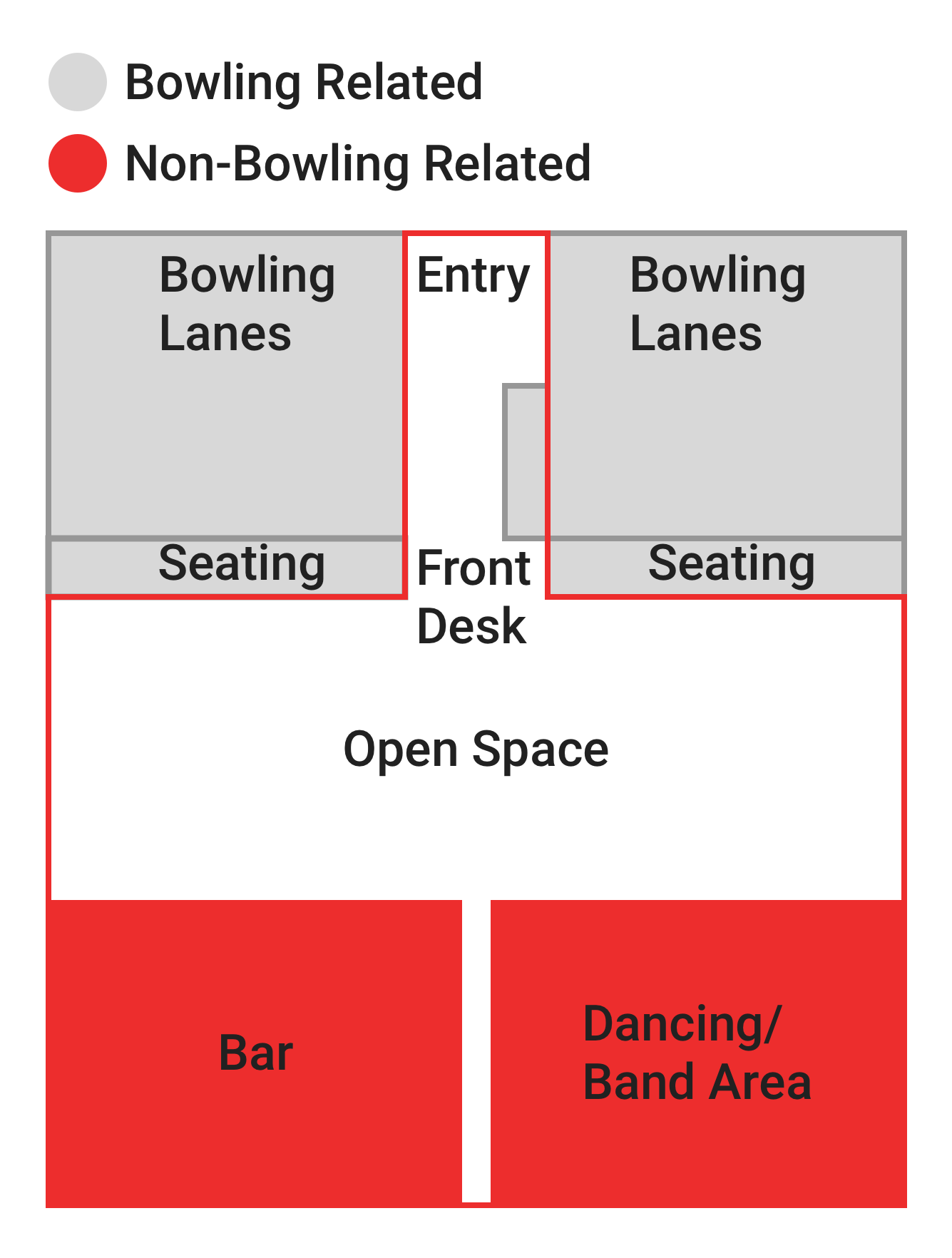

Although bowling alleys do not seem to have much trouble filling lanes, they do have issues filling the areas that don’t have any association with the activity of bowling. The ‘premier’ bowling alley in Portland, Maine is outfitted with 4 different bar areas, a dancing/live music area, a table-tennis area that comfortably fits 8 tables, and a rooftop bar/food-truck that is big enough to fit over 100 people. When I visited the alley for my ethnographic research, with the exception of a bartender in one of the downstairs bars, all of those ancillary areas were empty. The amount of wasted space was more than double the size of the space dedicated to the bowling lanes. I sketched the first floor of this bowling alley below.

The obvious insight is to repurpose the copious amount of space dedicated to the open areas and to non-bowling activities, transforming it into additional lanes, which I’ve sketched below.

The obvious insight is to repurpose the copious amount of space dedicated to the open areas and to non-bowling activities, transforming it into additional lanes, which I’ve sketched below.

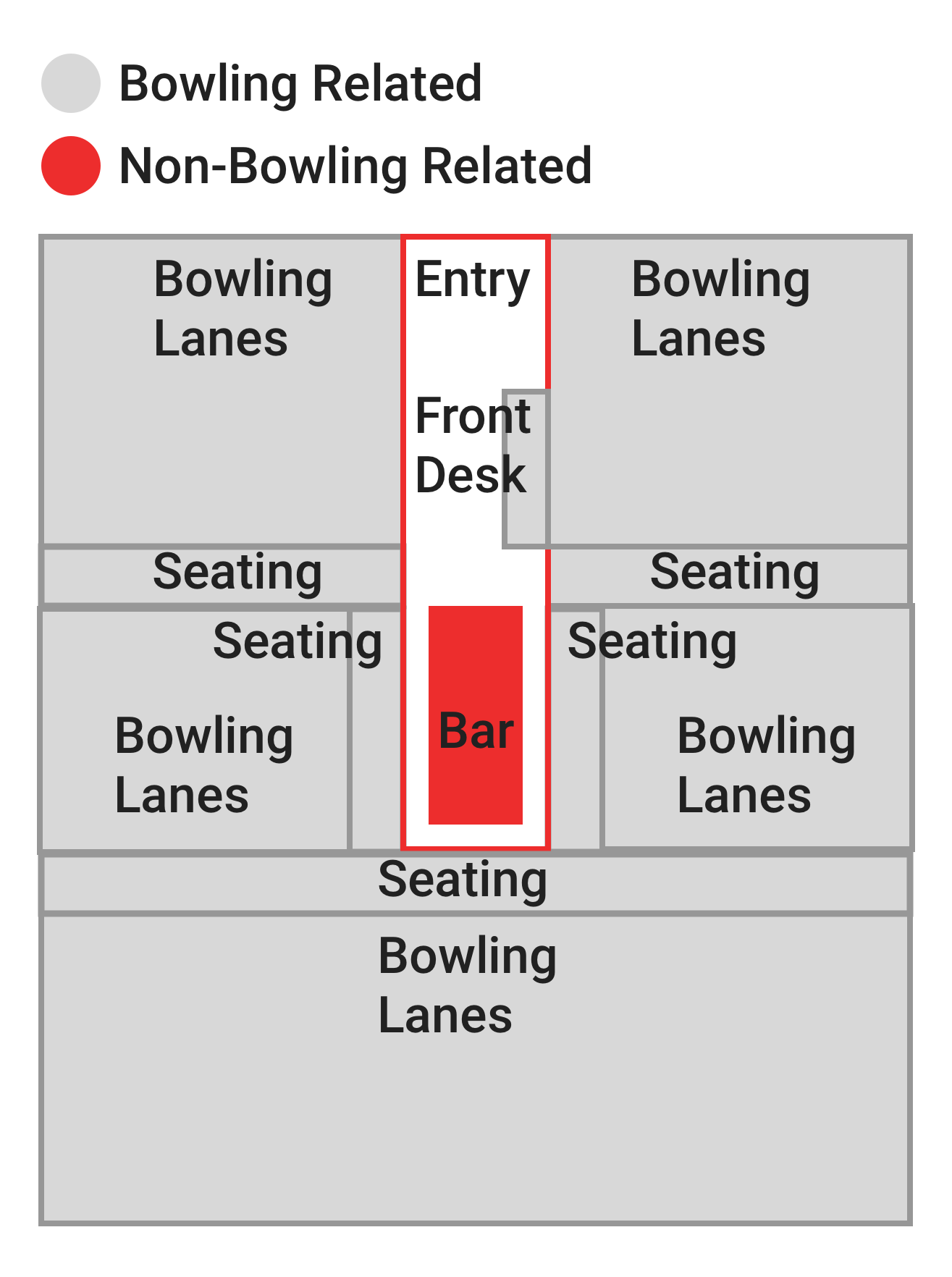

I’ve never been to a bowling alley with some lanes perpendicular to other lanes. It may take patrons some time to get used to, but even if the alley expanded a row of lanes across the current bar and dancing area, they could more than double the available lanes.

Many bowling alleys are structured in this fashion, with lanes on either side, a bar area, a ball purchasing area, and a desk to rent gear in the middle of the space. The alley closest to my home growing up was structured in this way. The real question is why these ‘modern’ bowling alleys, recently constructed and refurbished, chose to remove the additional lanes, replacing them with non-bowling activities.

Perhaps the owners and manufacturers of bowling alleys recognized the declining social infrastructure in our society and resolved to do something about it: repurpose space within bowling alleys to bring large swaths of people together. Or maybe I caught the alleys on a good day, and they’re not normally as packed as I witnessed, but all of my research showed that when people go to a bowling alley, they go bowling, perhaps eating and drinking with the group of people they’re with at and around their lane.

It’s a wonder bowling alleys in churches started stuttering in the 1980s and 1990s. Maybe it was a sign of the times. Religion was still popular while bowling was in freefall as a sport, but given the rapid decline in people who attend religious services in America (Mitchell, 2019) and the reduction of people hanging out, with the unused space previously dedicated to bowling alleys a recoupling shouldn’t be out of the question. Who knows, maybe if I hit a ‘Greek Church’ spare ![]() my mother will buy me the church.

my mother will buy me the church.

(MessyNessy, 2016)

Cameron, John, et al. The Big Lebowski. PolyGram Filmed Entertainment Presents, 1998.

Coppola, Sofia. Lost in Translation. United States: Focus Features. 2003.

Crockett, Zachary. “The Rise and Fall of Professional Bowling.” Priceonomics, 20 Mar. 2022, priceonomics.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-professional-bowling/.

Darabont, Frank, director. The Shawshank Redemption. Columbia, 1994.

MessyNessy. “Churches and Their Hidden Basement Bowling Alleys.” Messy Nessy Chic, 23 Sept. 2016, www.messynessychic.com/2016/09/23/churches-and-their-hidden-basement-bowling-alleys/.

Mitchell, Travis. “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 17 Oct. 2019, www.pewresearch.org/religion/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapid-pace/.

Rick. “How They Rolled 100 Years Ago.” Orange County Regional History Center, 14 Aug. 2021, www.thehistorycenter.org/how-they-rolled-100-years-ago/.

Robinson, Phil Alden. Field of Dreams. Universal Pictures, 1989.

Sim, Josh. “MLB World Series 2023 Is Least Watched on Record.” SportsPro, 3 Nov. 2023, www.sportspromedia.com/news/mlb-world-series-2023-tv-ratings-viewership-fox-texas-rangers/.

Stahelski, et al. John Wick. Summit Entertainment presents ; Thunder Road Pictures presents ; in association with 87Eleven Productions and MJW Films in association with Defynit Films, 2015.

Thompson, Derek. “Why Americans Suddenly Stopped Hanging Out.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 15 Feb. 2024, www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/02/america-decline-hanging-out/677451/.